The diff command is generally used for applying code patches. However, it can be almost as useful for comparing and merging two versions of the same text file.

To use diff on a file, it must be written in plain text or a markup language such as HTML. Otherwise, diff only tells you whether the two files are identical. The command syntax is standard:

diff OPTIONS FILE1 FILE2

For a long file, you may want to add |less at the end, so you can scroll back and forth through the output.

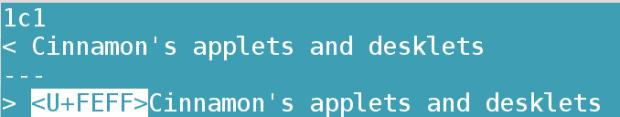

The output shows only lines in which the first file differs from the second file. The default output (Figure 1) prefaces lines from the first file with <, and lines from the second file with >. At the top of each pair of lines will be a notation such as 3c3, which means that, for the files to match, the third line of the first file must be changed (c) in order to match the third line of the second file. The output may also indicate that something needs to be added (a) or deleted for the first file’s line to match the second’s. A line of three dashes (—) separates one pair of differences from the next.

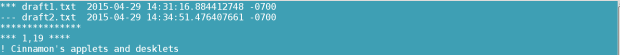

Alternatively, you can add the -c option to provide a context view (Figure 2). A context view arranges information differently from the default view, showing file information at the top, marking the first file with *** and the second with —. A separator of multiple asterisks follows. Below the separator is a range of lines that need to be changed, plus the lines around them to help you identify the context. Lines starting with ! are ones that must be changed, while those starting with + must add text, and those starting with a – must delete them. Somewhat confusingly, the information is given first for the first file, and then for the second.

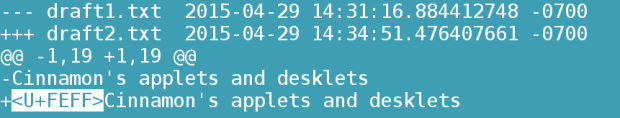

Still another option is the -u or unified view (Figure 3). The unified view is similar to the context view, except that changes needed for both files are positioned together.

In addition to these choices, you can use -y to display the two files in side by side columns. Other options filter the output — for example, ignoring white space (–ignore-all-space) or letter case (–ignore-case), or excluding specific strings (–exclude=PATTERN). About the only option in the man page that isn’t equally useful for text as for code is –show-c-function.

What diff essentially does is create a script for merging the two files together. When using text, you can use the output manually, opening it in one window and the first file in a text editor and run through the changes, accepting or rejecting them as you choose.

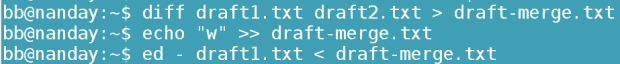

If you simply want to accept all the changes in the second file (Figure 4), you can save diff’s output to a file with:

diff -e FILE1 FILE2 > MERGESCRIPT.txt

echo “w” >> MERGESCRIPT.txt

Here, the first command creates the script, while the second alters the script so that it will write the changes. You can then use the ed line editor to apply the changes :

ed – FILE1 < MERGESCRIPT.txt

Using diff for ordinary text requires some learning, but the process is no more laborious than approving changes in LibreOffice or any other desktop application. In fact, using diff is easier than several of the desktop collaboration tools that I have seen. My advice is that you choose the diff view you prefer, and gradually build up a set of options to use.

[sharedaddy]

Excellent article. diff -c is brilliant!