A play on the Audi slogan: Vorsprung Durch Technik. Except we’re going to talk about something that is clearly not progress. Systemd. Roughly 6 years ago, Systemd came to life as the new, event-based init mechanism, designed to replicate the old serialized System V thingie. Today, it is the reality in most distributions, for better or worse. Mostly the latter.

Why would you oppose progress, one may say. To that end, we need to define progress. It is merely the state of something being newer, AKA newer is always better, or the fact it offers superior functionality that was missing in the old technology? After all, System V is 33 years old, so the new stuff ought to be smarter. The topic of my article today is to tell you a story of how I went about fixing a broken Fedora 24 system – powered by systemd of course, and why, at the end of, my conclusion was one of pain and defeat.

Background story

We all know that people are resistant to change, so sometimes, it is difficult to differentiate between legitimate opposition to inferior products and a kneejerk emotional response. This is why changes need to be measured in the same way biology measures its success. We need to look at the evolutionary model and apply it to technology. We need to ask, is the new stuff really better? And it comes down to how easy it is for a new product to survive – in the hands of its users, and how much investment is needed to sustain a successful level of existence. If you’re looking for an even more abstract analogy, it’s about energy. Any new model ought to be even more energy efficient, and require fewer resources to maintain the optimal, often minimal level of survival.

This model is highly relevant and applicable to software, much more than you may imagine. Take a look at Windows 8, and the introduction of the Screen Menu, which effectively doubled the number of actions required from users to access common things previously available in the classic desktop setup. This increase in effort without any increase in productivity led to a huge backlash from the community, and eventually, Microsoft went back on its decision and restored the standard menu, because it is superior on the evolutionary scale.

The same thing applies to Windows 10 settings versus the old Control Panel. Close to home, the Gnome desktop environment is another good example of an evolutionary regression. Opening applications takes an extra click, as they are not readily available on any workspace or panel. Some of the criticism may sound petty, but it touches the core of what we are, as a human race. We are biological engines, and we are designed to be lazy.

If you have never used System V like, eh, systems, before, then you probably won’t care about Systemd. However, if you have performed system administration tasks on a Linux box in the old era and now need to do the same with Systemd, then you might be interested to know how much extra effort, apart from the obvious learning curve, you need to keep your systems healthy and going. This ties into our example. We have a broken Fedora box. And we want to try to fix it.

My ailing system exhibits the following symptoms – it cannot reach the Gnome desktop environment. It is stuck booting, and there are no indications as to what may have gone wrong. There are no virtual consoles available, and thus, I am unable to access any sort of debug information in order to try to resolve things.

The problem in more detail

So, the system is not booting. We only have the progress bar, which slows down as it reaches the right end, and then it never transitions into any kind of logic screen or desktop. Using Ctrl + Alt + F1-7 or any combo thereof does not help in any way.

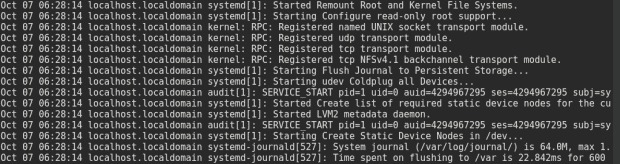

I realized the only way I was going to make progress was to boot into a Fedora live session and try to figure out from there what went wrong. This meant accessing the disk and mounting the filesystems first, which required a little bit of hackery, as I was using the default LVM setup. But as I’ve shown you in a tutorial on exactly this very topic, it’s not too difficult. In the live session, once I had the original /var/log available, I could finally see the root of the problem:

[FAILED] Failed to start Journal Service [DEPEND] Dependency Failed for Flush Journal to Persistent Storage

This is a Systemd message, and it tells us that something went wrong with the journaling service, which is governed by the journald daemon of the Systemd framework. At this point, I had to invest a lot of time and read on the finer details of the new init system, as well as a dozen forum threads discussing the issue. Unfortunately, everyone had an ever so slightly different manifestation of the problem, and the suggestions did not bear any fruit. Moreover, there wasn’t a single educated thread of information, more sort of trial & error guesses and hunches as to what should be done.

This led me to a troubling realization that the documentation and general knowledge on Systemd are very rare. There just isn’t the abundance of tips and tricks like you could find on System V, which would help you almost immediately narrow down your problem and resolve it. The problem affects both official sources as well as the Internet collective. The reason is quite simple though – Systemd is too complex for its own good and everyone forced to use it.

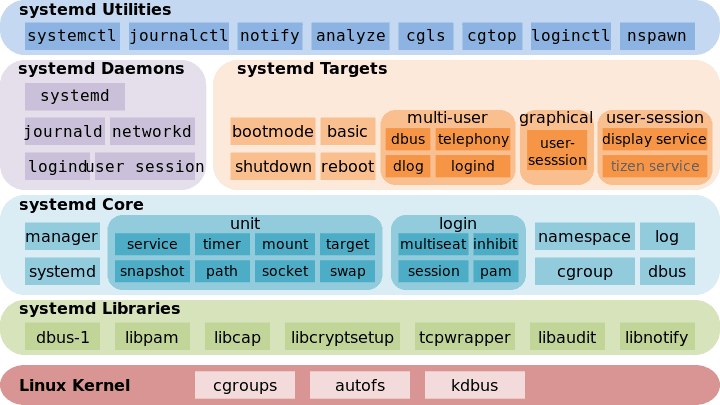

The number of components is just overwhelming – you have daemons, targets and core elements, as well as utilities. Targets touch into the user messaging systems, graphical interface and even the user session. The effort needed to master Systemd is probably equal to mastering all other components of a typical Linux system. This breaks the simplicity principle on which Linux is built, and it also highlights the development-focused nature of the framework. Systemd is a technology designed to make development easy, not necessarily the end usage. Now, let’s go back to our example.

Why Systemd is not suited for purpose

I decided not to give up and do some more work on my own. The boot log was not sufficient, and I had to open the journal logs and read what is inside. This turned out to be much more difficult than ever before. Systemd does not keep logs in a simple way, nor does it utilize flat files. Nope. You get binary files, with an internal database structure. This probably makes it easier for developers to do their work, it makes it impossible for administrators to troubleshoot.

When you’re running in a live session, you want the absolute minimum of tools to be able to debug your box. Alas, Systemd requires its own journalctl utility as a broker for reading and interpreting the information. Now, do not get me wrong, System V was not without its foibles. Pacct is a good example of complexity gone mad, but there, the binary method was required to cope with a huge volume of data. Systemd could use a simple method for booting, but because it is such a complex and inter-dependent framework, the boot process was sacrificed for the sake of all other components.

Now, journalctl normally expects the default root to be used, so you actually need to use –root or –file flags to open files that are not part of the running system. Again, this complicates access to logs, as you need to sort-of chroot into a different filesystem. The location of logs and the naming convention is counter-intuitive. To access the logs I needed to cd into:

/run/media/liveuser/<mount point>/var/log/journal/<unintelligible journal id>/

Then, here, you have user and system logs, labeled user-<userid>@<random-numbers>.journal and system@<random numbers>.journal, respectively. There are also the user-<userid>.journal and system.journal files, which should be identical to some of the previously mentioned entries. Moreover, the journal ID should be unique and persistent across boots, and if you get different numbers for multiple entries, then you may have a problem, which could be the reason for the earlier boot failure.

However, while this sounds easy when explained – it is very difficult to decipher while troubleshooting, and it is also not meaningful in any way. The numbers and the naming convention make sense from a purely transactional database perspective, similar to what you would have when working with cloud object storage, but not when you need to debug problems as a human. Moreover, we still have not accessed these logs.

After I located the logs, realized they were not accessible as text files, and used journalctl with the –file option, I then started going through the log to try to understand what may have gone wrong. The log files are very difficult to read. They also do not break over multiple lines, so you do not actually get the full output. Worse yet, I wasn’t able to find a single line that indicated of any problem.

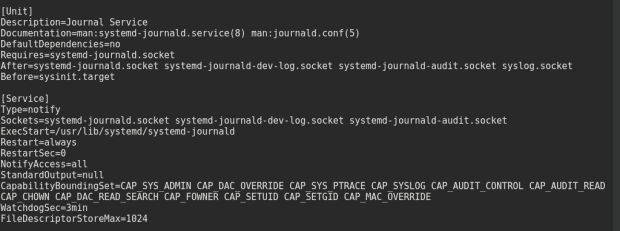

I then spent more time reading online, including Arch, Fedora, Mageia forums and other sources, to no avail. One of the suggestions mentioned a bug with journal persistence – hence the different random numbers in log files, which was the result of a wrong service type defined in the Systemd journal service unit file. I decided to explore this in more detail and see if I could fix it.

Unit files are similar to old System V RC files, explaining what each service needs to do when starting and stopping, except they are written in a far more convoluted way. The location of the unit files is also controversial, as they are located under: /usr/lib/systemd/system/<service name>.service. Specifically for the journaling daemon, the name corresponds to systemd-journald.service. I would expect system files to be located under /etc, especially when it comes to configurations. The new model breaks a well known convention.

In the unit file, I looked for wrongly declared directives – specifically the Service type should be set to Notify, which it already was. However, other than blindly bumping around after spending roughly two hours chasing solutions online, I was nowhere near closer to understanding let alone resolving my problem.

Intuition

I believe I’m a highly technical and tech-savvy person with a very good intuition around technology. I am able to learn and test new things and concepts with very little need for manuals, help files, online sources, wikis, or any other types of information. I can sit down and start using the software immediately, and this has always been the case. Good examples include KVM, Docker, and others, none of which are trivial. However, Systemd completely stumped me. It is one of the few technologies that has no regard to previous experience, knowledge or ability to work logically. It is designed as a dimensionless framework with an object-oriented approach to events and triggers, and as such, it does not follow the basics of logic that is imprinted in our brain. It is software that is best suited for AI, never for human interaction.

At the end of the day, I had learned a few things around Systemd, but very little of any practical value. I had mostly uncovered various flaws in the design, which I’m sure can be easily self-justified. I had realized that Systemd is complex, difficult to use and read, and not very helpful in solving problems. Indeed, my Fedora box remained unbootable, and I was forced to rebuild the installation. I do not recall a single case where I was unable to fix a Linux box when it was still powered by good ole init. I had worked on some really bad issues, but I was always able to recover. With Systemd, I had to concede defeat. The notion of events and timeouts is just completely wrong. And it goes against the Darwinist principles of evolution, be it biology or software.

Conclusion

We cannot stay in the past. We must change. Unfortunately, sometimes, future solutions fail to deliver, because they are trying to fix a problem that does not exist. I’m sure a ton of developers can easily point to a hundred flaws in init, but that does not mean that Systemd is the answer. The same way the internal combustion engine has its merits 130 years after it was created, System V and init are probably not ready to be relayed to history, especially not when Systemd is the current proposed alternative. It simply does not have what it takes to be the superior functional and evolutionary replacement.

It is a change, but one that introduces a huge amount of energy into the environment, and it offers very little to no practical advantage over the previous implementation. This is true of many other recent changes in the Linux world, including the windows system, the audio framework, desktop environments, and more. The trend is quite alarming, as it is enabled and led by new technology, but not necessarily innovation. The two are not necessarily mutually inclusive or given. And that is the distinction that seems to have eluded the Linux world a lot recently. It is evident in the decline of popularity, stability and acceptance of Linux distributions, most likely because the focus is on re-inventing that which does not require any.

As far as Systemd is concerned, I am concerned, because it is a technology that does not correlate to knowledge or experience, and it poses a great risk to the prosperity of Linux. Evolution has its ways of telling us when we’ve done something wrong, so it will be interesting to judge what is happening today15-20 years from now. I do not foresee bright times. And you might as well practice Linux installations, since they may be the answer to when Systemd goes bad, as I cannot foresee any easy, helpful way out of trouble. Stay strong.

[sharedaddy]

As an IT professional who almost exclusively uses Windows systems at work but who likes to explore other systems for fun (and when the occasional Apple device requires attention from me either professionally or for family) I can understand how hard it is to be forced to do a reinstallation to fix a problem. It always bothers me when Windows “IT pros” recommend a reinstall to fix this problem or that. In my opinion it is a lazy way out and more importantly, you learn nothing about why the problem happened and why the solution actually solves the issue. To say nothing of the fact that you begin to make users expect that your OS is fragile and must be “refreshed” just to keep it properly running. Even when a reinstallation makes sense for clients (time is money after all) I will often attempt to take a system image so I can work out the problem on my own time. In any case, this was a rambling response but I really enjoyed your article and understand the frustration of being left without an answer. Learning new things during a repair is one of the great things about being in IT in the first place, it is a shame when effort is expended and there is little sense of problem-solving satisfaction. Please keep up the articles and your site, I love to read every new adventure! (Even when it is yet another underwhelming distro review). Thank you!

I don’t know if this is a manifestation of the same issue, but recently, my Manjaro XFCE partition hung on boot, after a systemd update. The 32-bit version of this distro was so badly mucked up, that I needed to reinstall.

The day after this fiasco, the Manjaro developer published an advisory, recommending that folks update systemd first (and separately) from the rest of the updates. I followed his advice, and systemd updated properly, and the rest of the updates installed without issue.

I realize that I didn’t bother to investigate the root cause of the problem, but I’m an enthusiastic amatuer, rather than a professional. I was happy with the work-around, which saved me much time and trouble. The 32-bit version of the distro is a test-bed, so I lost nothing by re-installing.

Systemd has been working OK otherwise, but in general, I see no reason for its existence.

So, about your statement of the GNOME Desktop being an evolutionary regression because it takes an extra click if one needs an application not ready from the panel.

This argument is nonsense and dumb, both theoretical and practical.

On the practical level, it doesn’t matter if in practice, because of the ready availability of the most-used apps, there is less work needed compared to other desktop environments. If the overall net result is less clicks, then it is better. And it is less clicks for the overwhelming majority because 99,99% only uses their few standard apps!

On the theoretical level, less clicks is not the only measure. If sometimes a click more is more logical, easier to understand, this may be preferabele. Ease of use is and should be the parameter! And maybe speed, and that’s where GNOME is superior to all. Because experienced users just use the SUPER-KEY and type the first 3 letters of the app and ENTER, even before the results are visible, and the app is starting within tens of seconds! Beat that!

I advise and install a LOT of GNU/Linux for the elderly and noobs and I’ve use all of the DE’s. They ALL prefer GNOME 3, without exception! Most of them are astonished by the ease of use, beauty and simpleness.

Also, when introducing GNU/Linux, never underestimate the WOW-factor as maybe one of the most important factors in marketing and spreading the freedom. And that’s where GNOME 3 is king of all Desktop Environments!

“the app is starting within tens of seconds! ”

Yes, I had fun about my mistake too 😉

Obviously, it should be tenths of seconds!

You are wrong. Most users don’t actually use the “most used apps” feature and in any of the OSes. Same goes for “Most recently used files” feature. People don’t just go to a computer and think “I do what I do most”. They don’t. They think about a problem in their office or in their environment and this is what occupies their mind. So they look for the application to solve the problem with. It’s simply unnatural to think in terms of going back doing what you’ve been doing the most.

what bothers me about systemd is that input for you and others about how to make it better or the problems that it has has largely been ignored.

I’ve been watching the talks about systemd and there is hardly any good talk about it. I was sceptical at first like many others, as I have come to love the simplicity and openness of the init scripts and I didn’t see the need that some had to get rid of it.

I am generally a fan of micro management and not of macro management and find micro management to be easier to get into and also to get back into after some time has passed. Hence my love for the old init system. Macro management always requires one to consider all factors simultaneously and one false change can bring it all down. Newer versions of a software with new options or even changed options make macro management a nightmare for me where I find myself studying the entire documentation just to make sure I’ve picked up every new detail and don’t make mistakes where I find myself hopelessly lost in search for the cause. This is not so with micro management solutions where mistakes stay contained and makes learning and managing changes into smaller tasks.

Still, I’ve been giving systemd a fair chance as I don’t want to be one of those old timers who never change. Now I wish I could say everything is working fine with my Debian/systemd, but it’s not. What at first appeared as a win in boot time of 7-8 seconds has come down to a mere 4 seconds. The old init needed 15 seconds to boot up and systemd is now back up at 11 seconds.

The shutdown times have however increased dramatically and I often get a 90 seconds message about a stop job running for a couple of users. I’ve searched for a solution to this problem a few times, but other than it being some kind of bug has there not been any consent among the users as to what exactly is causing this issue and so no simple work-around is being offered.

What I’ve learned from this experience is that I am fine with only a few seconds boot time. A difference of a few seconds mean little to me now and I am fine with systemd not being as fast as it was initially. I do however value the old shutdown times and find times of over a minute not acceptable.

I do like the “service ” command, because it is a bit shorter than typing “/etc/init.d/”, but for the same reason do I dislike the “journalctl” command and because I still read through the majority of log files with only “more”. “more” just never seemed wrong to me and I find it absurd that this now needed a new command, one with 53 individual command line options. It’s again micro management versus macro management for me and I find myself reading through lots of options just to find the one option that I need or to realize it doesn’t actually hold the solution to my problem. With “more” do I know where I am at. It has a minimal number of options, none which I actually need, and yet do I keep using “more” basically everywhere and all the time. That’s how valuable it is to me as a command. This is why I most of the systemd commands don’t appeal to me.

By the way, the “systemd-analyze blame” command is the funniest of the new commands by the way. The new generations seem to have much greater love for blaming someone or something than the older generation (they could have just called it “times” but went for “blame”…). Not that the command in itself is of much value, since I’ve stopped caring for seconds or just milliseconds in differences.

systemd is not a bad piece of software, but it seems to me as if it was written by young and eager people who are all to willing to make an early mark in their lives, but then avoid growing with it and not seeing it through. I wonder how many more years it takes for systemd to get its “childhood issues” sorted out. But I am also surprised to see how a project, which was initially condemned as bad and evil, didn’t turn around and opposed the nay-sayers, but ends up producing bad news over and over again. That’s untypical for the open source community and I’m hoping it isn’t becoming a trend.

What is really funny is how Dedoimedo is telling us to use RedHat distros (specifically CentOS or Fedora) and complains about systemd, created by RedHat developers (Lennart Poettering).

Although I don’t like or use the RedHat derivatives, (because I’ve found them too restrictive, and balky with my hardware) and I find Dedo’s struggles with those derivatives somewhat ironic, I realize that he uses them, because they work well with his set-up. I’m sure that others that use RH/derivatives appreciate his efforts.

Freedom of choice is what makes Linux/BSD so attractive to most of us.

I suppose this was your attempt at making a smart comment. Only you miss that what he does is what many people do. One can like something as a whole, but dislike individual parts.

Quite a large number of RedHat Enterprise or derivative (CentOS/SL) distro users are unhappy with systemd. We expected the grown-ups at RH to not allow such a dumb mistake to make its way through Fedora, but the inmates seem to have started running the asylum starting back around F15.

A lot of pain could have been avoided if systemd had been nipped in the bud back then.

I guess some accounts are just auto-promoting bots for IBM Red Hat. But you can ignore them safely – there are no real genuine systemd lovers. You can see this on twitter – compare the “systemd sucks” twitter group with ANY other “pro-systemd” group (if you can find the latter). Then you know how many people do not like systemd – it is a huge number.

“We must not forget that the wheel is reinvented so often because it is a very good idea; I’ve learned to worry more about the soundness of ideas that were invented only once.”

— David L. Parnas (Why Software Jewels are Rare, IEEE Computer, 2/96).

“A learning experience occurs whenever the Universe says to you, “You know that thing you just did? Don’t do it again.”–Douglas Adams

The reviews and criticisms of systemd have not changed over the months. What can be done about it? How are you Linux geeks going to get rid of it?

You can use linux just fine without systemd. I know because I have done so ever since IBM Red Hat forced its way onto Linux.

All the complexity built onto systemd helps the paid corporate hackers around systemd maintain their job, sell support etc…

It is essentially a milking machine for them.

Admittedly you now have less choice than before thanks to distributions betraying users and forcing them into systemd, but you still have choice of pure, systemd-free linux distributions. And the linux kernel does not yet have a hard dependency on systemd, but you can be sure that IBM Red Hat will be trying. Who knows for how much longer Linus can stand strong – having shares of IBM Red Hat makes him biased.