A few weeks back, we talked about a bunch of things that Linux could do better. A total of eight sore points. Does not sound like a lot, really, and surely, it does not cover everything that might need fixing in Linux. Some of you also remarked that most of the items also apply to other operating systems. Sure thing, but it’s our favorite bunny we’re discussing here.

Anyhow, since there’s still more wrong to be fixed and good to be bettered, let’s follow up with a sequel. To wit, this article, and we’ll have a go at a few more problematic aspects of the common Linux usage, which, if mended, would surely make our favorite platform that much more pleasant.

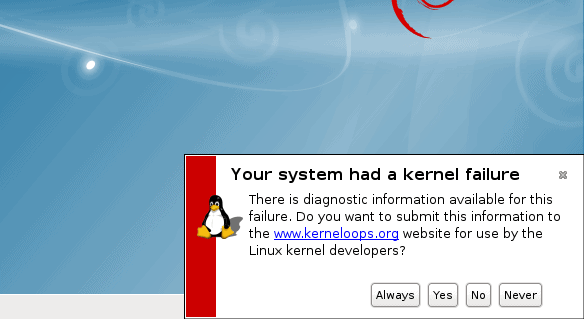

Kernel crash collection in the live session

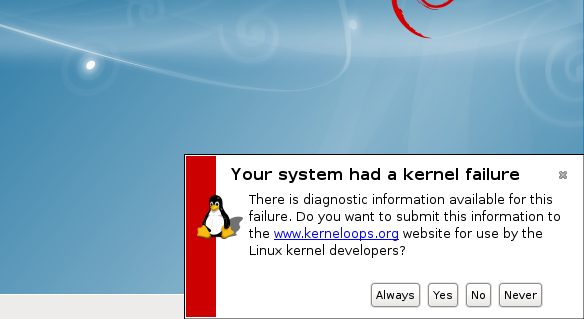

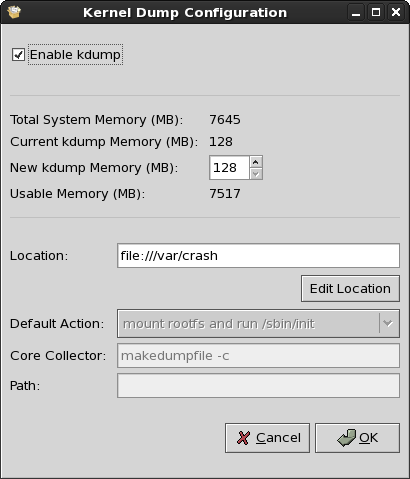

I think the biggest missed opportunity in Linux is not configuring the Kdump mechanism by default. This is true for installed distros, even more so for live systems. Think about it. Whenever a new distro version is released, people download the ISO image, burn it and start exploring. Sometimes, they encounter bugs, which simply go unnoticed, because they won’t bother reporting the problems, partially because the existing tools that do that are somewhat cumbersome and intrusive.

On other occasions, a whole system may go down, oops or panic style, and apart from the blinking Caps Lock LED and a hard boot, you won’t be able to do much to diagnose the issue. I had this very issue when testing Fedora 19. Approx. five minutes into the live session, the system would suffer a kernel panic, and the best I could do was take a photo of the monitor, showing the crash stack. The actual memory core was not preserved in any way, and I had nothing useful to send the developers.

However, collecting these crashes is one of the more important things of a distro life cycle, because it can shed a lot of light on the stability of the system, and allow the developers or the vendor to introduce necessary fixes. The quality of Linux would improve as a whole, much faster.

Today, very few distributions bother setting up Kdump, at all. In most cases, your system will not have a sane mechanism of collecting data and reporting it upstream. Compare this to Windows, where the system is configured to write minidump files to the disk, without user intervention.

Language support

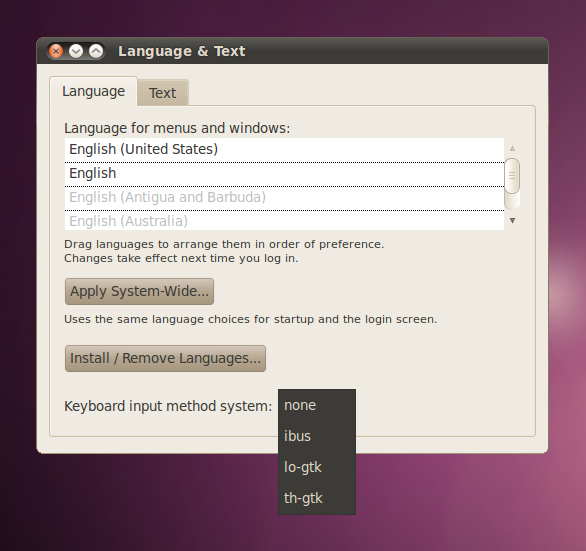

Most of the people in the world speak more than one language, and consequently, type more than one language. When they need to change their keyboard layout, they need to burrow into the system menus and find the right options. Unfortunately, this process is far from being a pleasant international escapade, especially for Far East Asian and RTL languages.

Until very recently, pretty much every single distribution would botch it, offering three or four complementary tools with the same functionality. Furthermore, you would be bombarded with questions, options, geeky lingo, and other uncool stuff, all of which have seemingly been designed to hamper your effort to enjoy good regional support. It has improved a little recently, but it’s a long way to the top if you wanna play Linux, AC/DC style.

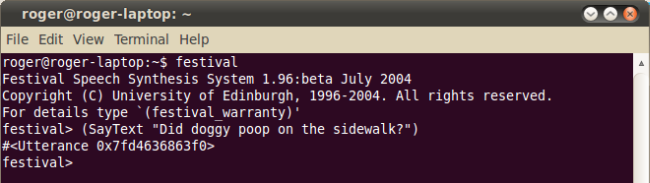

Speech synthesis

Trivial, right? Well, no. For visually impaired people, this is not a matter of slight inconvenience. And while there are a few tools that do well in this regard, like Orca or Festival, overall, the integration of speech synthesis in the Linux application framework is very weak. Neither the setup, nor the usage are immediate, plug-‘n’-play style. Furthermore, most applications are not designed with speech synthesis in mind. From what I recall, and I might be mistaken here, only Knoppix Adriane ever offered a default text-to-speech interface.

While this kind of work may not be glamorous, I believe there should be a strict definition of usability and accessibility, through the entire application stack, built into the different desktop environments, so that helper tools can be used with extreme ease. Finally, dozens of fairly useless synthesis applications that lurk in the repositories ought to be pruned, because they are an insult unto the effort.

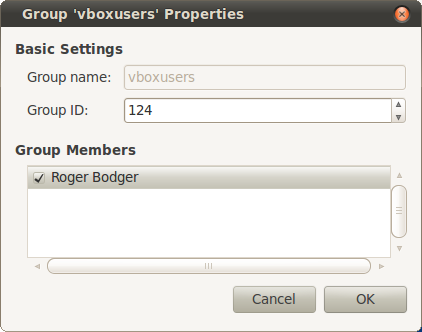

Groups and permissions management

If you don’t know how Linux works, you may sometimes feel a little confused about how you may gain permissions to use certain devices or applications, without having to elevate your privileges or suffer from weird errors.

So how do you do that? Command line? Sure, that’s doable, but that’s not the point. Some kind of GUI? Well here, it becomes complicated. There are many different ways you can go about managing users and what they can do, and no two desktop environments offer the same, consistent way of doing it. Worse yet, some expose only a subset of available options, others hide things on purpose, and you really must understand what you’re doing to get the desired results. While there are certain security implications involved, it ought not to be that complicated.

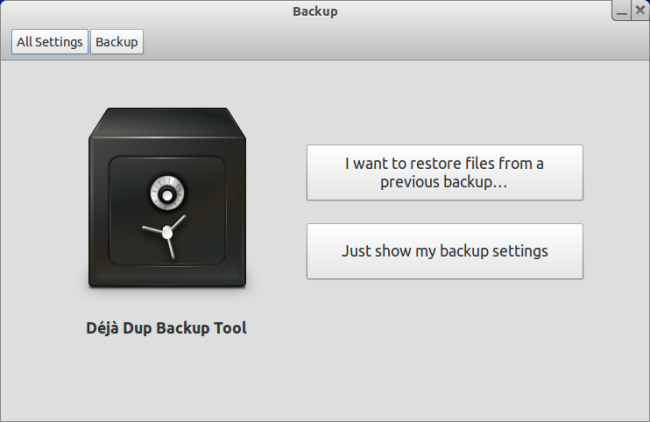

Backups

You boot your favorite Linux distro, you polish it to perfection, and what now? In the best case, you will keep your data separate in its own /home partition. In the worst case, you will do nothing about. If you’re really adventurous, you will try to create some kind of a scheduled task that copies your personal files to another disk or a remote storage location, and it will run once a day or once a week, something along those lines. If you trust the cloud, you will setup a cloud service.

What unifies all these methods is your personal insistence on data backup, rather than a solid distro policy of having a robust mechanism in place, which should protect your stuff from accidental loss. I think that all systems should come with a combined local and remote backup utility that would be launched after installation, offering users the chance to create some kind of a plan that will keep a second copy of their personal information on another drive or host. Moreover, this should be done in a smart and possibly standard manner, so that you do not need to relearn everything if you hop a distro. An initial post script would be sufficient, something like what Crunchbang Linux does.

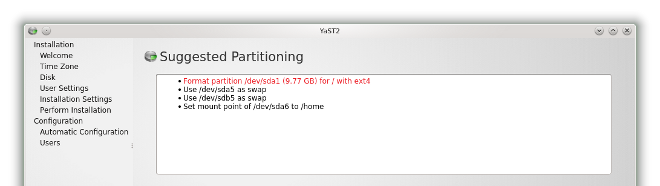

Safer installations

Once Linux becomes super popular, it will be sold preinstalled on purchased hardware, so this item may yet become irrelevant sometime in the future. For the time being, most of the Linux deployment base comes from installations performed by the user. Not a trivial thing if you already have data on your local disk, and now there’s a chance you might delete and ruin it, right.

Most distributions do offer fairly benign partitioning procedures, mostly consisting of shrinking large partitions, moving data about, and creating new ones. However, often, these suggestions are far from ideal. In my opinion, the only distribution that offers really wise setups is openSUSE. The rest just try to juggle stuff about. Even so, you have a lot of margin for error in this critical step, and this includes deleting partitions and formatting your data. Having multiple ‘Are you sure’ prompts can lead to increased levels of anxiety and paranoia, but it hardly counts as a good way of preventing data loss.

Personally, I think that the data setup should include two levels of verbosity. For professionals and skilled users, keep it as is. For newbies and fresh converts who do not have a geeky friend around to help them, there ought to be an abstract separation between physical storage and what they might try to achieve. In other words, the users should not need to know the disk notation and labels, they just need to figure out what kind of layout they want for their data.

Then, based on the actual storage limitations, the right choices would be made, which may include deletion and creation of partitions or data, shrinking of existing devices, or even creation of filesystem containers on top of existing partitions. Somewhat like WUBI. This might not be optimal, but what do you do if there are no free, available partitions, and the user’s one and only Windows partition is crammed full of fragmented data? Dump the system into a container into the existing space, and forget about performance and elegance. That’s a way of doing it, without compromising the existing installations.

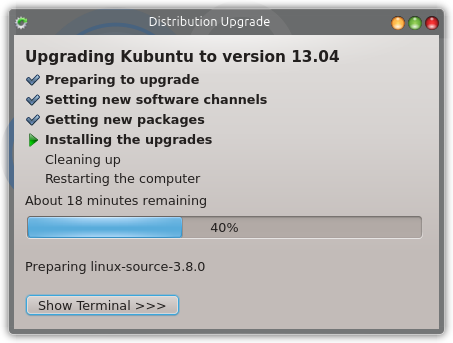

Planned obsolescence

When it comes to support, Linux has the widest of spectra. From just nine months for most modern distributions to ten years and more for the enterprise flavors. However, regardless of how long your support might be, you do not really know, especially in the home market, how your desktop will evolve or change.

For instance, half the tools you are running in your LTS release might be gone by the time the distribution reaches its end of life, so you will only get occasional security patches, if that, and no enhancement or bugfixes of any kind. Some distributions will purposefully hold back updates, others will maintain software revisions for as long as they deem necessary, and none of them will tell you what to expect.

The end result of the rapid change in the Linux app sphere is that the install base changes between one release cycle to another, spring to autumn, and your music players and office programs come and go. Not the most relaxing way of ensuring a good user experience. So what ought to be done is make sure that software is not just supported, i.e. dumped into a repository and periodically updated, but also officially supposed by the application developers for the entire duration of the distribution cycle.

In other words, if you want your program to be included in the repository of a certain distribution, you must guarantee support for as long as the distribution plans to support itself. For the interim releases, this is hardly reassuring, but for LTS and longer-lived flavors, this could be a good way of securing user trust. To make it even more interesting, distro vendors ought to force application developers to actually support their software for at least two or maybe even three distro cycles or five years, whichever is longer. This way, a lot of one-off efforts would vanish, reducing clutter, and you’d be left with sustainable, high-quality software that has a future. Users would then know when their software is going to die, and not just their distributions, allowing them to make necessary adjustment for switching over or trying other programs.

Conclusion

More grudge from Mr. Happy man, Dedoimedo. Well, it all depends how you look at it. The list presented here can be treated as criticism, or it can be construed as a way of improving Linux, so that it becomes better, safer, smarter, more elegant, and user friendly, for all segments of the society. For me, the most critical items are the first and the last, because they directly impact the stability and predictability of the operating system. Once you have those, you’re in control, you know what you’re doing.

Furthermore, comparing (too much) to Windows or OSX would be a mistake, because the business model is different. However, try to think of the few things that people interpret as professionalism. It mostly has to do with how their data is treated, and what gives them a peace of mind. Hardware is another important element, but it’s not Linux per se, more sort of how Linux is used. That does not mean we have to wait. We can start improving the existing bunch already, so once we slap our improved system on dedicated hardware, it will rock.

Cheers.

[sharedaddy]

If Linux was a BSD distribution, it would be perfect.

If BSD were a Linux distribution it would still suck.

That’s because it was a Linux distribution.

For back-ups I image the linux partition and save it to my external drive.

That’s a KDump pic from CentOS/RHEL, eh, where you can enable it at the conclusion of the install?

I always did, and I never had a single problem with those kernels.

Too bad GTK on RHEL/CentOS is so old, and that it doesn’t respond well to the Infinality treatment ( at least at my hands.(

it’s now effectively 2014, so after 15-20 years of numerous distros, why won’t linux(MINT 13) INSTALL MY PRINTER automatically??? Geez, open a terminal? I’d rather open a vein !!!!!! Linux will never become mainstream until it can do these simple jobs painlessly. end of rant.

WhaaaAAAT?????? “INSTALL MY PRINTER automatically???” who does that?

It installs my networked printer at my shop just fine, no terminal needed. In fact I can install the printer faster and easier on Linux than I can on Windows 7.

You are a moron.

Interesting, I wrote about different languages in Linux recently: short how-tos for different desktop environments:

http://linuxblog.darkduck.com/2013/11/how-to-configure-keyboard-layouts-in-xfce-cinnamon-mate.html

http://linuxblog.darkduck.com/2013/10/how-to-configure-keyboard-layouts-in-unity-gnome3-kde.html

Here’s my biggest gripe about Linux: Take your brand new Z87 chipset computer with the latest/greatest of everything. Now, try to put any release of your favorite distro that’s older than 2 years old. It won’t even boot! Now, fire up a 2001 copy of Windows XP… It not only boots, but installs! Why can’t Linux be made to do that?

Your mileage will vary with the kind of distros you try and how updated they are.

I’ve had hardware on which ringtail won’t boot but ancient centos 6 will. 😐

It’s all about drivers support. Windows XP will install, but you’re only going to get it truly working depending on OEMs and their drivers.

You can do the same with Linux, I doubt you will get one that won’t boot unless they’re trying to do something tricky. I can get freeDOS to boot on anything.

This was actually a rather balanced and insightful entry. It’s good to see something like this amidst the slightly more opinionated (though undoubtedly interesting) posts that are common here.

YES. I have had serious issues getting multiple language support in Linux for a very long time. Even if I can find the language I need, I get hit with “no input window” messages or I have to switch between two (or more) IMEs for different languages. For this reason and this reason alone I was always forced to go back to OS X, which does multiple languages without screwing around. However it’s looking like Gnome 3 is finally getting it right. I still have to do more testing, but so far I can use the languages I need easily in Gnome 3.

I use a program called Timeshift for my backups. It’s kind of like a best of both worlds combination of Windows system restore and Mac OS Time Machine. You can even restore from another distro if you try one out and don’t like it.